Image generated with DALL·E through ChatGPT

Opinion: Low Earth Orbit Is Getting Too Crowded And It’s A Problem For All Of Us

For years, I’ve heard about thousands of satellites orbiting the Earth, like those relentless clouds of mosquitoes that swarm travelers on tropical vacations or in parks during the summer. But the Earth isn’t on vacation—it’s dealing with this every single day. And the situation is more complicated than I thought.

Last week, the United Nations urged companies and governments to cooperate and work together to manage satellites. There are over 14,000 satellites—over 6,700 belong to Elon Musk’s Starlink—and more than 120 million pieces of space junk in orbit and that number is only expected to increase. Also last week, multiple European space companies—Airbus, Thales, and Leonardo—announced a new partnership to compete against Starlink with more satellites and similar services.

While the tech innovation is exciting and more and more necessary—satellites help us communicate globally, get oriented with our GPS, predict the weather, and entertain us with Internet connection in remote locations and TV shows—low Earth orbit (LEO) is getting too crowded.

And there’s a serious downside to this situation, there’s an increasing risk of collision and the consequences are seriously concerning.

The Current Situation

We are probably more dependent on satellites than we think. As a person who heavily relies on Google Maps to walk around any city, or Waze to drive alone anywhere, I now subscribe to this statement.

The impact satellites have in modern society is massive and governments and companies are relying on it more and more. Italy recently announced a partnership with Starlink to provide Internet services in remote locations, and Apple is planning on bringing satellite connection to Apple Watch next year to allow users to send messages without internet or cellular connection. There is news every week about new satellite launches, services, or research developments with this technology.

Satellites Can Crash

It’s hard to see satellites from the ground, especially from big cities with heavy light pollution, but they are there. I remember spotting dozens of satellites one night in the North of Chile, in Valle del Elqui—a world-class destination for stargazing—, but there’s no need to travel to clear skies destinations to understand this phenomenon, it’s actually better to see it online as you can gain a better perspective and understanding of the problem.

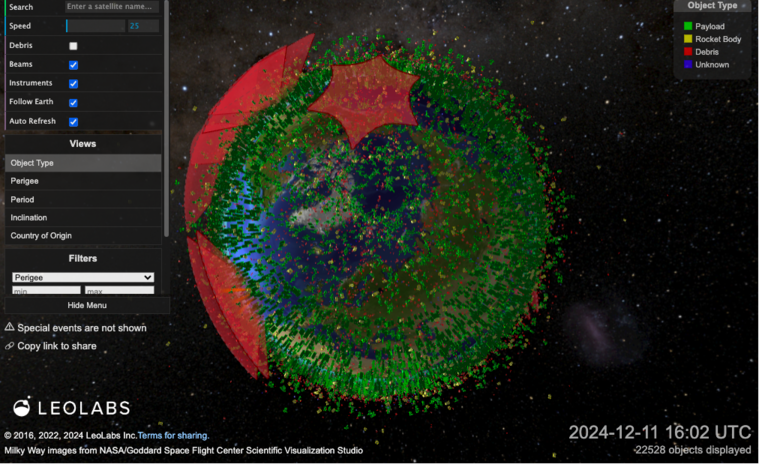

I recently discovered LeoLabs’ interactive map which displays objects in orbit in real-time and it’s a lot more terrifying than my fun outdoor experience. With up-to-date data, LeoLab—a company specializing in tracking objects in orbit—allows visitors to use the map to zoom in and out, filter, and sort objects for educational and research purposes.

After seeing that map the big question can easily pop to our minds: How can they all stay in orbit without crashing? Thanks to inertia and gravity—and probably luck at this point. Satellites are strategically placed, at a precise speed, in order for them to stay in their orbital paths and are monitored and surveilled by multiple organizations, but these organizations are worried too.

The fear is justified. Experts have registered crashes and dangerous situations in the past years, and there have been many challenges along the way. Space debris—produced by human and natural activities—and “dead” satellites—many stop functioning in just a few years—are hard to predict and control.

Science journalist Marina Koren wrote a brilliant piece for The Atlantic published in June explaining that two important satellites—one from Russia and another one from the USA—almost crashed this year. She interviewed scientists and a few experts confessed to getting very scared. They agreed that the consequences of this happening could be “disastrous,” and the risk is imminent.

If more satellites collide, many things could happen. From losing our functional smartphones to not being able to pay by card to having hundreds of flights canceled—remember this year’s glitch in Microsoft Cloud that created chaos across airports worldwide? Well, something like that. In the worst case scenario, we could face the Kessler syndrome, a hypothetical phenomenon where satellites and debris crash continuously until Earth orbit becomes unusable for satellite technology.

Can’t We Just Fix It?

Well, it’s not that easy. Designing a system that all nations and enterprises can agree on and rely on is a huge challenge. Different countries have their own rules and laws about space, and information about satellite positions isn’t always shared openly.

According to recent data from WorldAtlas, the U.S. has a record of 247 military satellites in orbit, followed by China with 157, and Russia with 110. These devices have powerful technology like sensors and high-resolution cameras that help with communications, precise locations, and surveillance information. Do you see these three countries sharing real data on their military satellites? Me either!

Companies might also hesitate to give away details about their spacecraft, considering it sensitive business or security data. Agreeing on a global set of standards means bringing together all players at the same table—an almost utopian idea considering today’s complex political environment.

Signs Of Hope

But there is hope. Multiple organizations are working on solutions for the crowded LEO traffic and on ways to reduce space debris. LeoLab’s radar network is helping track satellites in real-time, and alert organizations, and they are working with the U.S. government to improve and develop their system.

The European Union created a Space Traffic Management program to reduce space debris with international agreements, research operations, sustainable rules, and safety measures to improve space traffic. The European Space Agency (ESA) committed to a ‘Zero Debris approach’ by 2030 making companies and governments take care of their trash.

“We are aiming for rules that compare to every national park on Earth – what you bring in you must take with you when you leave,” states ESA’s website.

Other companies like the Swiss startup ClearSpace and the Japanese Astroscale are developing “space clean-up” missions to remove debris and dead satellites. But these methods are expensive, require fuel, and more space travel. Cleaning service as a space business is still in a very early stage.

To achieve balance and a sustainable system for orbital traffic around our planet, a combination of strategies, international alliances, and perhaps a touch of luck is required. Current initiatives hold great potential, and although we are still far from achieving it, it seems that with persistence, effort, awareness, and determination, a solution is within reach.

Previous Story

Previous Story

Latest articles

Latest articles

Leave a Comment

Cancel